BWEYOGERERE, Uganda – The Uganda National Bureau of Standards (UNBS) is set to ban the export of unprocessed maize that lacks a Q-mark (quality mark) and an SPS (Sanitary and Phytosanary) permit. This decisive measure aims to combat pervasive aflatoxin contamination and elevate the standard of Ugandan grain in regional and international markets.

The upcoming ban was highlighted Thursday during a training session for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) at the UNBS facility in Bweyogerere. The UNBS and the East African Grain Council (EAGC) are collaborating to equip businesses with crucial knowledge and skills in safe grain handling, testing and grading.

Patricia Bageine Ejalu, UNBS deputy executive director for standards, explained the rationale behind the ban, emphasizing the significant challenge of aflatoxin contamination in maize, a staple product in Uganda.

“Aflatoxin primarily develops due to improper handling practices during harvesting, storage and subsequent processing,” Ejalu stated. “We want to teach people the correct practices to prevent this. It’s simply about keeping products clean. This isn’t rocket science; it’s about following achievable steps at different levels of the supply chain.” She underscored the specific responsibilities of farmers, grain aggregators and flour processors in ensuring product safety.

Ejalu stressed that while food safety isn’t about “absolute perfection,” it demands continuous learning and implementation of practices to minimize hazards to an “absolute minimum, to a level that will not cause harm.” She noted that standards require contaminant levels to be “as low as reasonably achievable,” urging constant vigilance. “When producing food, you hold people’s lives in your hands, making this constant diligence paramount,” she asserted.

The UNBS is currently training its inspectors in preparation for the new directive. “The goal is that once this is implemented, anyone wanting to buy grain will need to purchase it from a certified dealer,” Ejalu explained. “This means our local producers must be ready; they need to have their produce certified so our neighbors can buy directly from them. We aim to eliminate the market for substandard products and maintain control over our produce.”

Though initially slated for February, the full implementation of this new certification requirement has been delayed to allow for thorough staff empowerment. Ejalu anticipates an official start date announcement between July and September of the next financial year.

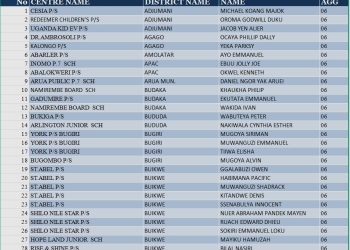

Approximately 25 participants from various SME enterprises countrywide, primarily those responsible for quality control and grain handling, are attending the training.

Paul Ochuna, country program manager for Uganda at the Eastern Africa Grain Council, highlighted the severity of post-harvest losses, noting that more than 40% of harvested grain is lost due to poor handling methods, with smallholder farmers often struggling with proper sorting and drying.

“The purpose of this training is to upskill the industry, as we’ve identified a skills gap among grain handling officers,” Ochuna said. He explained that the training, developed by experts, forms a core part of the Grain Business Institute curriculum and includes an online component administered by Iowa State University, which participants have already completed. The practical sessions offer hands-on training in grain sampling, testing for moisture content and grading according to standard specifications. Participants who score at least 80% on the online modules will receive a certificate.

Ochuna also detailed the EAGC’s innovative Grain Business Hub (GBH) model, which supports SMEs. Through the GBH model, smallholder farmers are organized into groups that then form cooperatives or enterprises. These groups receive extensive capacity building and institutional strengthening, with a strong focus on governance and management. The EAGC also employs a “training of trainers” (TOT) model, empowering GBH managers to provide daily advisory services to smallholder farmers on good agronomic and optimal post-harvest handling methods.

Beyond training, the GBH model facilitates crucial market linkages. It helps smallholder farmers access reputable agro-input supply companies for improved seeds, enhancing yields and productivity. The EAGC also connects GBHs to financial institutions, having signed memorandums of understanding to ease access to financing for farmers from production through harvest.

“We promote and support collective marketing, which begins with aggregation through the GBH model,” Ochuna explained. The GBH management encourages more grain to move from individual households into cooperatives, increasing aggregated volumes and strengthening collective bargaining power. Once these farmer-based organizations are linked to markets — both local and regional, leveraging the EAGC’s presence in more than 11 Eastern African countries — they utilize the EAGC’s standardized trading system, effectively connecting buyers and sellers and fulfilling the council’s mandate to promote structured grain trading systems.